Dec. 30, 1933 – Oct 21, 2020

H. Jesse Arnelle, Pathbreaker in Corporate Law, Dies at 86

Thirty years after he led the Penn State basketball team to the Final Four, he and a friend started one of the few Black-owned firms catering to blue-chip clients.

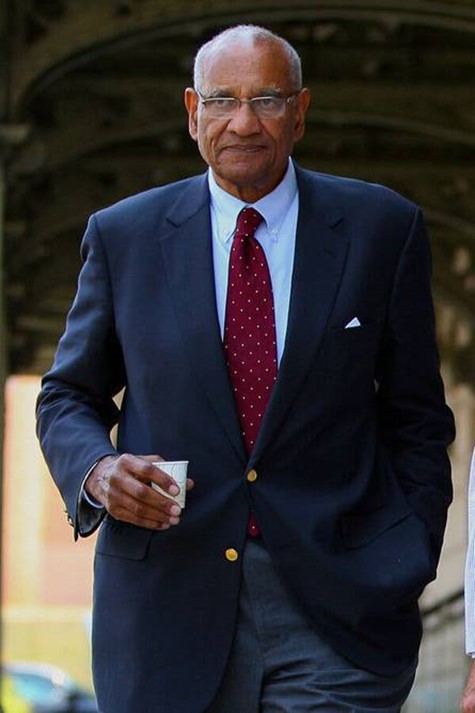

H. Jesse Arnelle, who helped start one of the first minority-owned corporate law firms in the United States three decades after gaining acclaim as a two-sport star and the first Black student body president at Penn State University, died on Oct. 21 at his home in San Francisco. He was 86.

His wife, Carolyn Block-Arnelle, said the cause was congestive heart failure.

Historically, Black lawyers had found little acceptance among blue-chip companies. They tended to gravitate instead to civil rights, criminal defense, personal injury and family law. But when Mr. Arnelle and William Hastie established Arnelle & Hastie in San Francisco in 1984, they wanted a corporate clientele.

“It was an audacious plan,” Mr. Arnelle told The New Yorker in 1993. “It was pretty darn presumptuous of two guys like us to say they were going into a corporate practice.”

Slowly they did, building a firm that at its peak had as many as 60 lawyers in cities around the United States and that served major corporations like RJR Nabisco (defending it in tobacco litigation), AT&T, Coca-Cola, du Pont, Chrysler, Levi Strauss and Merrill Lynch, as well as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation during the savings-and-loan crisis of the 1980s. The firm also started one of California’s largest public-finance practices.

“What we had was gumption,” Mr. Hastie said in a phone interview, “and we knew a lot of people.”

Arnelle & Hastie’s success led to recognition from Black Enterprise magazine as one of the nation’s top 12 Black-owned law firms. The magazine noted that Black firms still had to take “nickel and dime” work from corporations in the hope of securing more lucrative work.

The two partners, Black Enterprise added, “stunned clients with their courtroom skills.”

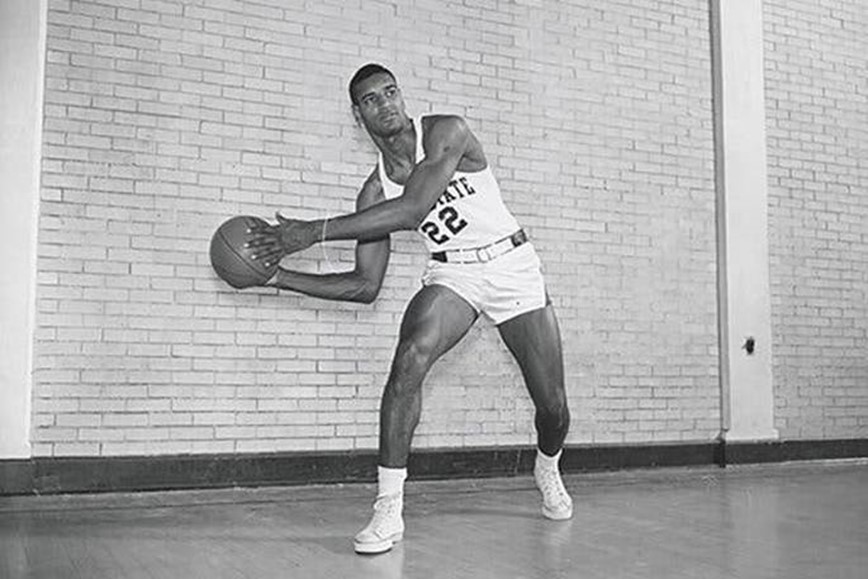

Mr. Arnelle — a power forward at Penn State who stood 6-foot-5 — was a charismatic figure, in a courtroom or a boardroom.

“He had an incredible trial and advocacy style and a great presence, which was partially his size, manner and deep voice, which you can’t undersell as a trial lawyer,” Mr. Hastie said. “He had a warm handshake and knew how to get close to people and listen — or appear to listen.”

Hugh Jesse Arnelle was born on Dec. 30, 1933, in New Rochelle, N.Y. His father, also named Hugh, had a hauling business. His mother, Lynne (Chevannes) Arnelle, was a domestic worker. The family, which included two other sons, lived in a government housing project.

At New Rochelle High School, where he was on the football, basketball and track teams, Mr. Arnelle stood out as “the guy, a quiet force of nature who was widely admired,” George Hirsch, a former classmate who is the chairman of New York Road Runners, the organization that runs the New York City Marathon, said in a phone interview.

Yet, Mr. Arnelle told The New Yorker, he was not as self-possessed as he seemed. As a sophomore, he recalled, he had come unprepared to a Spanish class and stumbled when asked questions by his teacher. After he left the classroom, feeling humiliated, his teacher, who needed crutches to walk, grabbed him and pushed him against the wall.

By his account, she told him that he had humiliated himself by not preparing adequately and said: “You have the ability to master any subject in the same way you have mastered that silly game you play — basketball or football or whatever they call it. I will help you.”

He was recruited by the Penn State football coach Rip Engle and played wide receiver for the Nittany Lions. He had greater impact on the basketball court, leading Penn State to the N.C.A.A. Final Four in 1954 (the team lost in the semifinals to La Salle University), and he was named most valuable player of the tournament’s east regional.

Over four seasons, Mr. Arnelle averaged 21 points and 12.1 rebounds a game.

In 1954, he was elected student body president with 74.5 percent of the votes cast. He graduated the next year with a bachelor’s degree in political science.

He continued his athletic career with a focus on basketball. Rather than play football for the Los Angeles Rams, who chose him in the 10th round of the N.F.L. draft in 1955, he played for the Harlem Globetrotters on an overseas tour, then joined the Fort Wayne (now Detroit) Pistons, who had taken him in the second round of the N.B.A. draft. He averaged 4.7 points in 31 games in his only season in the league.

After serving in the Air Force, Mr. Arnelle graduated from the Dickinson School of Law in Carlisle, Pa., in 1962. A job as a lawyer with the Labor Department in Washington led to a meeting with R. Sargent Shriver, the director of the Peace Corps, who assigned him to serve in Turkey, then to India.

When he returned to Washington, he worked on Senator Robert F. Kennedy’s 1968 presidential campaign before starting his legal career with a corporate firm in San Francisco.

In May 1968 — a month after the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and a month before Kennedy’s — Mr. Arnelle was invited back to Penn State to receive the Alumni Association Award at the annual football awards banquet. But he surprised his host by rejecting the honor and delivering a speech that excoriated the school’s record on race relations.

“For it is now more than a century since the commencement of this land-grant college and there has never been a Black American on the faculty with tenure,” he said. “There has never been a Black dean of a Penn State faculty; there has never been a Black vice president of the university in any capacity; there is no known Black Penn State graduate appointed, assigned or consulted at the policymaking level of the University.”

He added, “Should the university’s president call his immediate staff in conference, there wouldn’t be a Black face in the room.” Mr. Arnelle was named to Penn State’s board of trustees in 1969 and served for 45 years.

He continued his legal career as a trial lawyer for the federal public defender’s office and as the head of his own firm, where he practiced civil and criminal law for 15 years until starting Arnelle & Hastie. Mr. Hastie had also been a solo practitioner.

The firm remained independent for a decade, until it merged with another Black-owned firm, McGee Willis & Greene, in 1994. Mr. Hastie said the merger became a lifeline after federal banking work dried up, the affirmative action initiatives that had brought work from blue-chip companies faded, and some bond lawyers left the firm.

Mr. Arnelle remained at the combined firm until 1997, when he became of counsel to the law firm now known as Womble Bond Dickinson, which represented RJR Nabisco’ in tobacco litigation. Before retiring, he served on various corporate boards, among them that of Gannett, the newspaper chain.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by his daughter, Isis Bastet, and a son, Michael. Another son, Hugh Paolo, died in 2008. Mr. Arnelle’s marriage to Xenia Sorokin ended in divorce.

Mr. Arnelle recognized that his firm had sometimes been hired because the plaintiffs or witnesses in cases in which he was defense counsel were Black. But, he told The Los Angeles Times in 1994, he did not feel used.

“They made the same kind of value judgment I would have made: ‘Where can I best use the talents of this firm?’” he said. “That’s logical, good, lawyerlike reasoning. I don’t look on that as disparaging at all.”

—By Richard Sandomir (New York Times, Nov. 3, 2020 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/03/business/h-jesse-arnelle-dead.html)